Modern Camp: 3 Things to Consider When Building in a Hazard Area

The percentage of the US population projected to live near a coast is expected to approach 50% by 2020. The draw of these places is clearly stronger than the fear of the growing dangers generated by a heating and rising ocean - a testament to the inevitability of coastal architecture's importance. Building to co-exist with hazards has created great architecture throughout history. We think that good buildings respond to disaster not by retreating from it, but adapting to and learning from disaster; and that resiliency is what ultimately makes a place great over time. This is the first in a series on our study for the Modern Camp, a prototype for development in a changing coastal Louisiana and the importance to not reacting to hazards, but to owning and integrating them into a design.

1. ELEVATION

Crucial to all development in coastal Louisiana, and increasingly the coastal United States, is the elevation of the structure above the constantly shifting, and sometimes sinking, ground. FEMA guidelines are a good place to start, but many cities and parishes are looking at these as minimums that may be appropriate now, but insufficient in the future. Local governments may require a set distance ABOVE what's already required by FEMA - this is called 'freeboard'. Depending on where you are, your elevation could be the top of your lowest floor, or the bottom of your floor structure (if elevated). A good starting point to check the status of land you're looking to build on is LSU's Flood Maps project. In our case we have a minimum elevation of 11 feet, on land that is generally around 2 feet, creating a challenging opportunity to address a welcoming entry to a home 9+ feet off the ground.

To avoid having the gigantic staircase look of many elevated camp homes, we decided to break up the upward travel into segments. Grading the site to get a higher starting point, we have an initial ramp to an elevated platform, from which you can choose which entry to use. One ramps up towards the bayou views and the dog-trot guest house, while the stair entry heads around toward the main house entrance. The natural inlet is spanned with a boat house structure that provides access from both the boat's raised storage position and fully lowered position.

2. STRUCTURE

FEMA published a residential guide in 1984 (FEMA 54) and an updated version in 2010 (FEMA 4969) that outlines general best practices for building homes in high-risk coastal areas. Some of these principles can be seen already employed in vernacular camp design in the area. Piles extending up and through an elevated floor, for example, provides a rigid structure tied together by the floor structure than can be braced beneath the floor with sufficient room and protection. As piles are already generally needed throughout the Louisiana coast, continuing this structural system above ground makes sense. Locating the piles outboard of exterior wall envelopes alleviates some of the tolerance issues with locating piles exactly where walls need to go. Cantilevers for exterior walkways is an old strategy for increased efficiency when using a pole-frame system - less piles, more floor area. The guides are a good primer on basic strategies to consider with regards to site, structure and systems in a hazardous and changing environment.

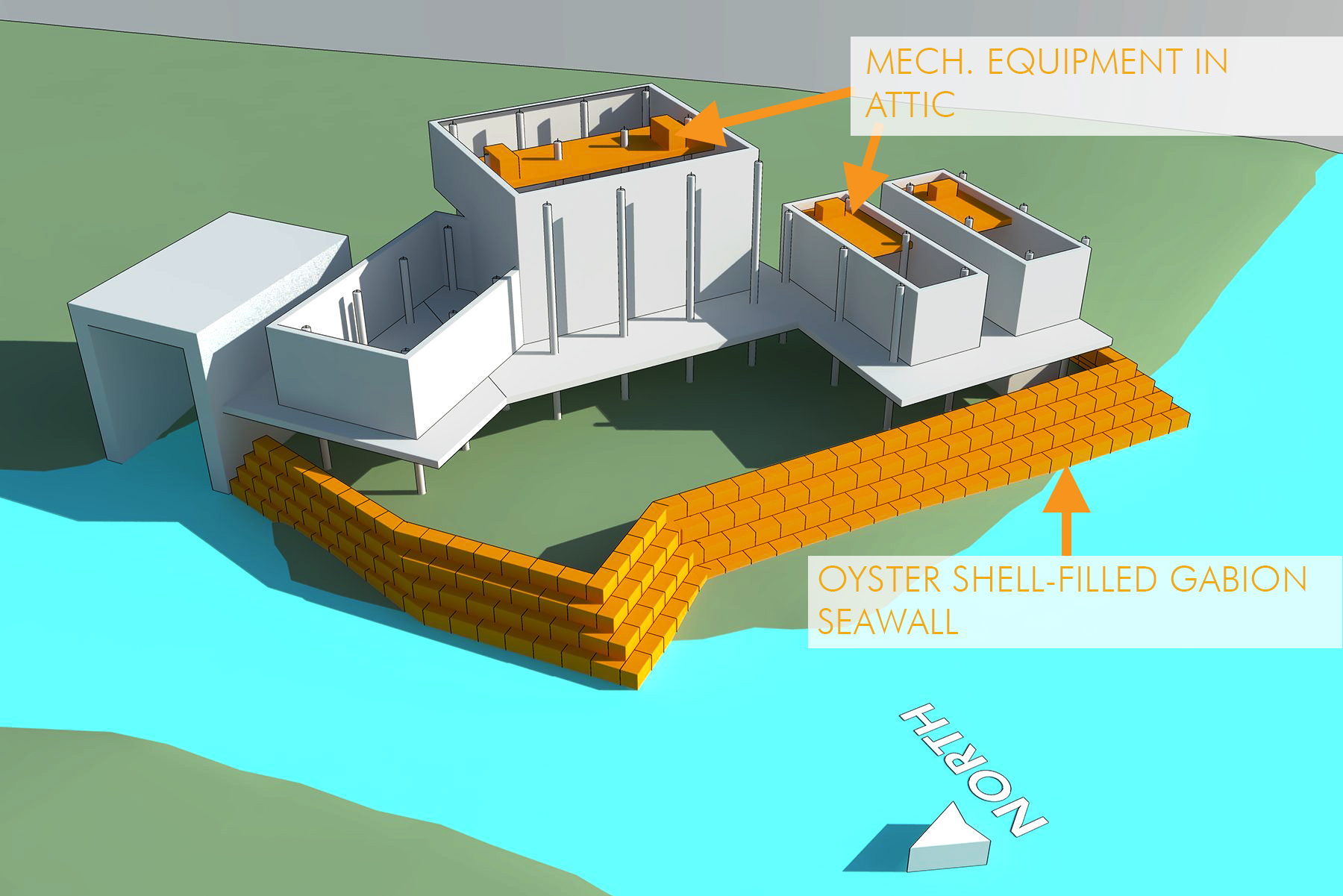

3. PROTECTION

In an emergency situation, with surging water, protection of what cannot be elevated is important. Siting behind natural berms and breakwaters is the cheapest option, but in order to site the building with water access, construction of a barrier will be necessary. Many of the homes along the bayou utilize sheet piling to retain the land and hold back the water, however, the issues here are evident in the many rusted out walls that can be seen. Steel and maritime environments do not mix without significant expense. Oysters do, however. In a strategy already deployed in many places along the Delta, oyster shells from restaurants are collected and repurposed as ballast for open cages called gabions, typically filled with rocks for civil projects at inland locations. These oyster-shell filled gabions are an effective seawall and protect the structure below flood elevation, as well as an utility lines, vegetation, vehicles, or anything that has to remain at grade. Any equipment that can be located high, is located high by using space-efficient systems in attic space, well above the reach of flood waters.

We'll continue later with our strategies on both passive and active energy efficient design in our series on our study of the Modern Camp!